Trees cut by the Donner Party at the surface of the snow in the winter of 1846-47

The Donner Party

Welcome to Weird Wednesday! Today we’re off on another of our ill-advised journeys—this time across the US Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1846, by wagon.

A few years back, my family made a cross-country move from the US midwest to the west coast, following routes pioneers took 175 years earlier. We made the drive in 3 (long) summer days. For settlers like the Donner Party, it could take up to 6 months, from spring to fall. Most importantly: our route was lined with grocery stores and restaurants. For the Donner Party, the lack of food would be famous—and fatal.

The Donner Party of pioneers, named for its leader George Donner, was doomed by a late start, interpersonal conflict, and one spectacularly bad decision: trusting two strangers about an untested “shortcut” on the way to California. The first stranger was Lansford Hastings, who urged the party to leave the Oregon Trail for his Hastings Cutoff. Hastings probably did intend to save travelers time, but the route was brand-new and Hastings himself was largely unfamiliar with it. (No, really.) The second stranger was Jim Bridger, who assured the Donner Party that Hastings’ route was easy, clear, and short. Surely it was just a coincidence that Bridger ran a supply post along the new route.

The truth was, Hastings Cutoff was actually longer than the trail it skipped, and grueling: the Donner Party found themselves hauling wagons up and down cliff sides by rope and trekking across the Great Salt Lake desert—80 miles with no water or grass for the oxen. A wagon train ahead of the Donners, on a slightly different route and guided by Hastings himself, made it to California. The Donner Party, already late, and delayed an entire month by this “shortcut,” did not. Many of them never would.

The last obstacle before California was the Sierra Nevada range: major mountains with wicked winters. The Donner Party, attempting the crossing in late October, met early blizzards that dropped 20 feet of snow. Eighty-seven men, women, and children were stranded, miles from help.

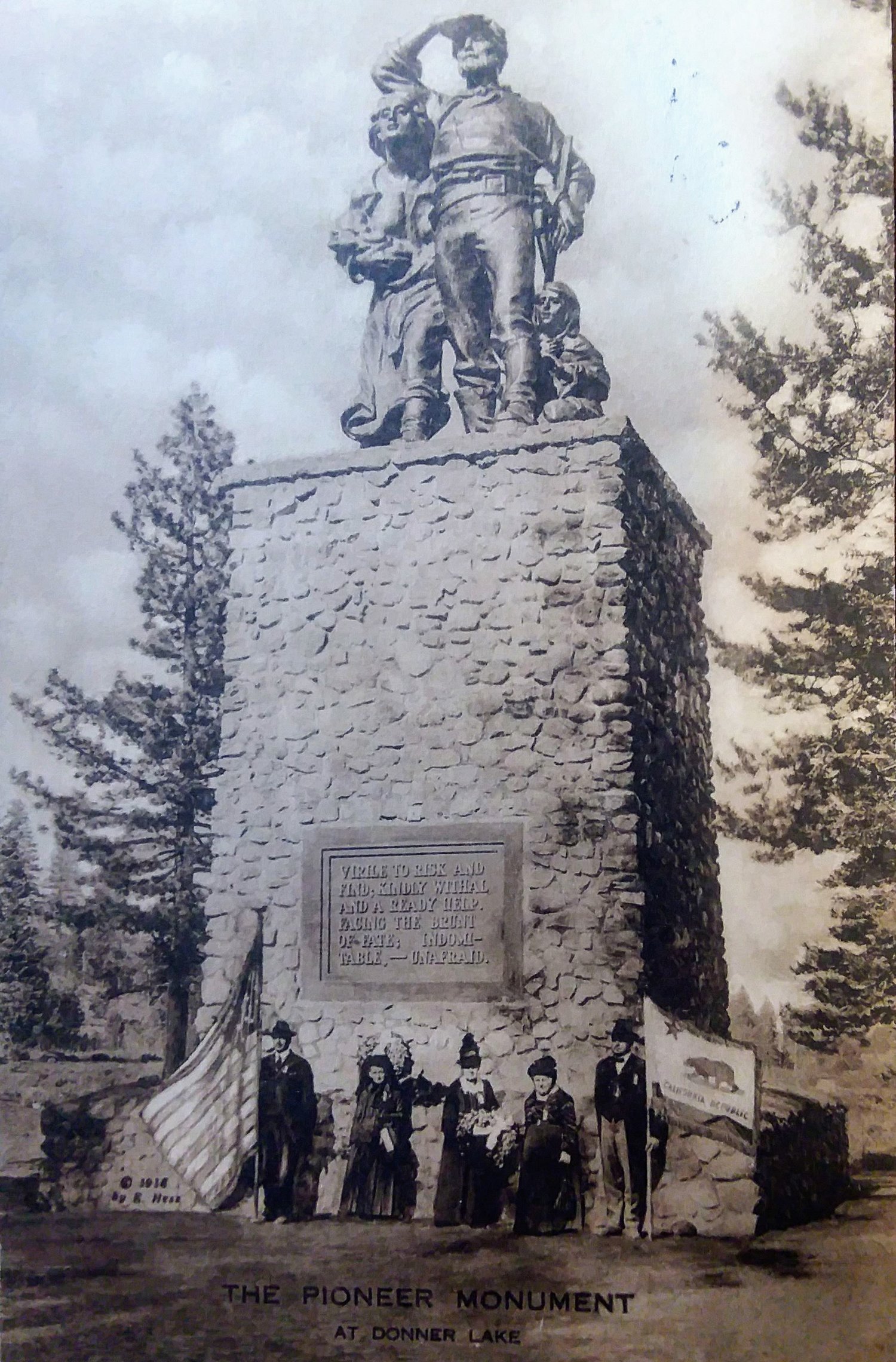

The Donner Party built basic cabins by what is now unsurprisingly called Donner Lake, and huddled there as the snow fell. Eventually, the group split into two parts: one stayed in the cabins; the other, nicknamed “Forlorn Hope,” attempted to cross the mountains on foot to reach help. At one point, the hikers made a fire which melted the snow around them, eventually depositing the sufferers at the bottom of a 24-foot hole of snow. People in both groups began to die.

Survival cannibalism is a tragic mainstay of wilderness and sea disasters. The focus, of course, is that people are eating other people, but to my mind what often gets overlooked is the incredible things people will eat right before they get to that point. The Donner Party ate shoelaces and horse bones boiled enough to be swallowed. Some children ate a rug. Eventually, they were desperate enough to eat their own cabin roofs, made of ox hides, leaving them without shelter.

There are two kinds of survival cannibalism. The first is usually palatable (sorry) to society at large: the eating of people who have already died. Both parties were faced with that decision, and many survived by eating the dead. But there are also cases in which people kill other people for food; this is what most likely happened to two Native American guides who were considered expendable by the pioneers.

Eventually, relief parties reached the stranded settlers and helped them get to California. Of 87 people stranded in the mountains, 48 survived. For a fascinating look at survival demographics, see Stephen McCurdy’s article Epidemiology of Disaster, 1994 [pdf]. (For example, don’t be a healthy young man, because you have no fat reserves and you’re expected to do more work.)

And now, who’s hungry for writing prompts?

-

Ghost train. It goes without saying that Donner Lake should be haunted. Some hauntings, known as residual hauntings, replay the past, as if trauma can record itself across time and space. Witnesses to a residual haunting at Donner Lake might see phantom cabins and snow, misery and death played out over and over. There are also intelligent hauntings—what we think of as “ghosts”— those who interact with the living, whose spirits might still be trapped where they died. Your story could have ghostly parents searching for their children, doomed lovers, or even phantom oxen. What would these ghosts be like? Grieving and dangerous? Or wise and protective of modern-day travelers?

- And then there were none. Lansford Hastings surely did not mean to get people stranded in the mountains. But you could write a story about a guide with a dark motive. Perhaps he wants to kill someone in the wagon train and is willing to have the entire rest of the group be collateral damage. Perhaps he hates the whole group because they slighted him early on the trail. Maybe he did something awful to deserve the slight, and he doesn’t want witnesses to make it to California. But in the Donner Party, roughly half the settlers survived. How would your villain handle it if his intended target/s didn’t die?

- It’s not too late. Today 16,000 people live by the shores of Donner Lake, in a town called Truckee. There’s a railroad, and of course, restaurants. It’s human nature to wish we could go into the past and use modern technology to aid doomed travelers, shipwrecked sailors, or plague victims. A time travel story about bringing the Donner Party into modern-day Truckee would be fascinating.

- Buried treasure. When people started out on the Oregon Trail, they had wagons full of belongings, with healthy oxen to pull them. But when they got a few miles down the road, the oxen began struggling, and people started leaving possessions by the roadside. If things got really dire, even wagons got left behind, which meant people had to carry everything on their persons—including money. And we’re not talking paper bills here. Pioneers buried heavy coins and other wealth all along the Oregon Trail, including at Donner Lake. Treasure (and morbid souvenir) hunters scoured the encampment when the snow melted and found gold. Some of the money made it back to those who’d left it, and some did not. Of course, they also found bodies and evidence of trauma. You could write a whole cast of characters revisiting the camp in summer, with a variety of motives and reactions to what they find.

- Cannibalism. The reason the Donner Party is so famous is that people are fascinated and horrified by tales of cannibalism. It’s hard to imagine being so hungry that you would eat literally anything, awful to think about the psychological effects of surviving on the bodies of family members or friends. A story could examine different characters’ reactions to facing that kind of choice. How would it affect their lives after they were rescued? Would they deny the evidence or feel a need to confess? Would cannibalism be the worst part of the ordeal for them, or might there actually have been something worse?

Thanks for visiting on this Weird Wednesday! No bad final joke today—unfortunately, hunger is still a problem all over the world. You can help by supporting your local food pantry.

Want more Weird Wednesday wilderness? Check out Disappearance in the Desert: Everett Ruess

Want to chat about the blog? Did you use one of the prompts? Hit me up on social media.

If you like spooky tales of the westward migration, feel free to check out Queer Weird West Tales, which contains my story The Train Ticket: A man holds a ticket to Hell after accidentally robbing a ghost train.

Sign up for my free monthly newsletter and never miss a blog post! Or subscribe by RSS

The Donner Party: Wikipedia

Survival cannibalism: Wikipedia

Rare Weather Trapped Donner Party in 1846: Tahoetopia

Great books about the Donner Party:

The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of a Donner Party Bride by Daniel James Brown

Ordeal by Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party by George R. Stewart

The Best Land Under Heaven: The Donner Party in the Age of Manifest Destiny by Michael Wallis