Why the Nederlander Theatre is Haunted:

Chicago’s Little-Known 1903 Disaster

Welcome to Weird Wednesday! Today we’re stepping back in time to the closing of the year 1903, and one of Chicago’s deadliest days.

Theaters are often said to house a ghost or two: a famous actor, a murdered understudy, a jealous lover. But the shadowed halls of the present-day Nederlander Theatre in Chicago are a little more crowded than that: try 602 ghosts.

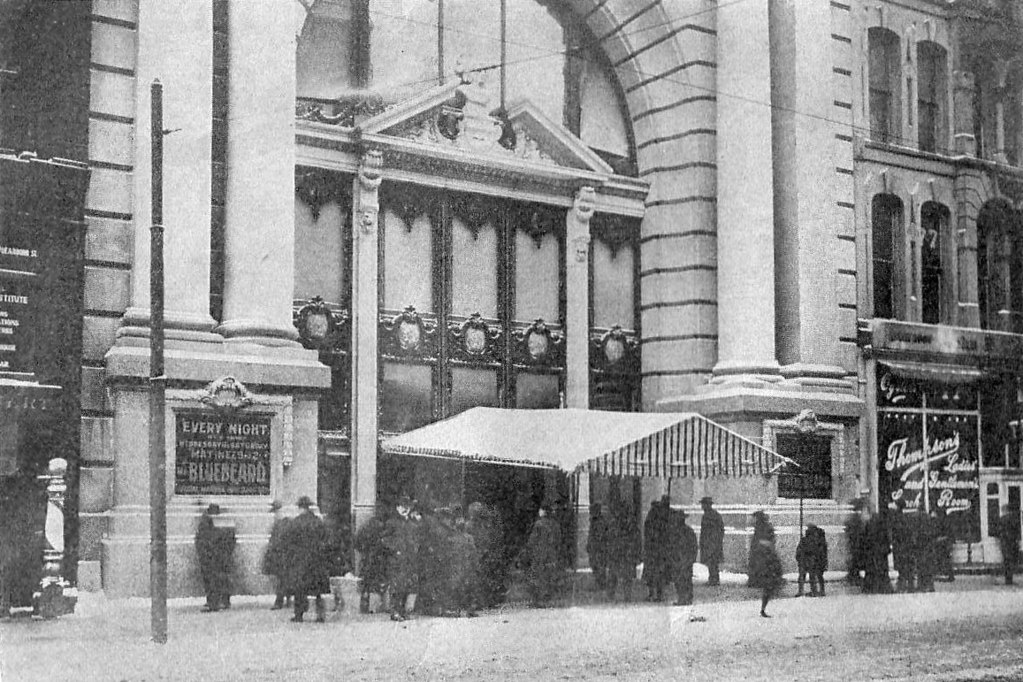

On Dec 30, 1903, a different theater sat where the Nederlander does today—The Iroquois Theatre, and it was the site of America’s deadliest structure fire.

The Iroquois Theatre was billed as “fireproof.” And to be fair, it was. On the morning after the fire, the theater stood, as gorgeous as the day before, with its massive stone arch and magnificent carvings. It was just everything inside that had burned: the elegant seats and draperies, the rich carpets and stage scenery—and 602 people, twice as many as died in the entire city in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

How could something like this possibly happen in such a beautiful place? How could so many people die in such a short amount of time?

Let’s take a look at what went so wrong that late December afternoon.

There are two ingredients to every major structure fire, from years before the Iroquois up to the present day. The first is complacency, and the second is a string of errors that cascade like dominoes, each small enough in itself, but together able to bring the horror of fire to a building full of innocent people.

On Dec 30, 1903, the Iroquois Theatre had been open for only five weeks. A touring company led by comedian Eddie Foy was performing the musical “Mr. Blue Beard.” During the performance, stage curtains got too close to an arc lamp, and the fabric caught fire.

Stage fires are actually not uncommon. In fact, nearly all theater fires start on stage, because that is where curtains, props, and lights are. Thus, we do actually know how to prevent theater fires from turning deadly. First, drop a fire-proof curtain between the fire and the audience, which will give them time to evacuate.

Second, open a skylight above the stage to draw the smoke out of the building instead of having it flow into the theater. Smoke makes an evacuation difficult because it’s not only hard to breathe, but it can also block the lights, meaning everybody’s trying to navigate an unfamiliar building in the dark.

Third, trained ushers should direct patrons to a nearby door, which should be unlocked and free of obstacles. It’s important to note nervous patrons generally will not like this. In a stressful situation, people will instinctively seek exit through the door they came in, because they know it works. However, if everybody’s trying to use that door, it can slow down evacuation. So ushers must show patrons to whatever door is closest to them.

Fourth, the sprinklers should go off and put out the fire, aided by employees who know how to use fire extinguishers. The fire department should have been automatically summoned by fire sensors, and they can do the rest.

Do all this, and you’ve got a great chance to reopen your theater in a few months after smoke and water damage are cleaned. There will be no lawsuits, no criminal trials. No funerals. If the Iroquois Theatre had done even one of those things successfully, we might not be writing articles about them 120 years later.

To their credit, the stage hands did immediately try to lower the fireproof curtain to shield the audience from the fire. But the curtain got stuck and would not lower all the way. In any case, it didn’t matter, because it wasn’t fireproof at all: the curtain quickly went up in flames.

Then there was the skylight, meant vent for the smoke. There was one above the stage. It was nailed shut.

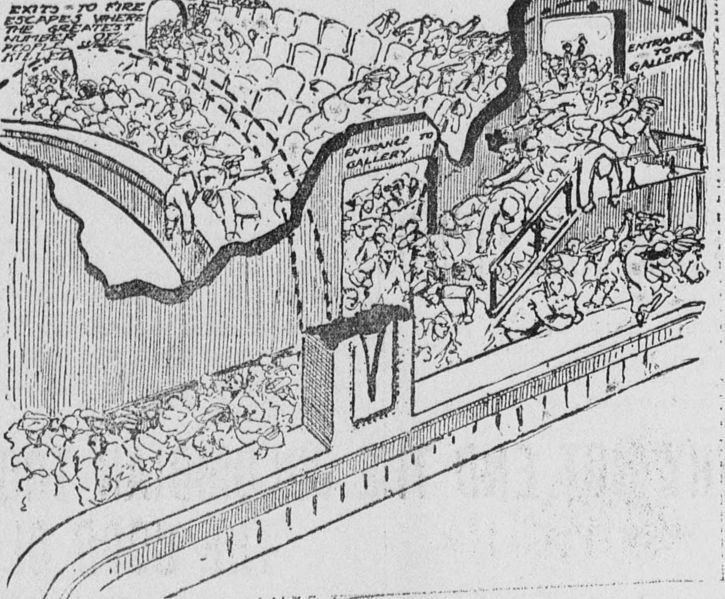

Exits were a catastrophe in themselves. An exit might as well be a solid wall if patrons can’t use it, and most of the Iroquois Theatre exits were unusable. Some were hidden by drapes. Some were locked with bascule locks, which look beautiful, but are very confusing. Some exits into other parts of the theater were blocked by gates, because the theater management didn’t want people who paid for the cheap seats sneaking into the fancier areas.

And then there were the stairs. The Iroquois Theatre had a split staircase which led from each side of the balcony before meeting to form one grand staircase down to the floor. It truly was gorgeous. But when two streams of fleeing people meet on a staircase, of all things, they are going to trip. And they did. The stairs quickly became impassable.

Artist’s conception of the staircase, artist unknown

Actors and stagehands fleeing the burning stage went out their most logical exit: a huge door that opened wide enough to allow the moving of massive scenery. The influx of cold Chicago air turned the flames into a fireball that went to the highest point of the theater: the second balcony, called the gallery.

And there were no sprinklers. There were pipes, but they had no water in them. There was no water on stage, and the few powder fire extinguishers that existed were useless in fighting a fire higher than people could reach.

It was a matinee performance on a weekday, so the audience was mostly women and children. They died of smoke inhalation, burns, and crushing near the useless exits.

And now we come to the other major cause of fire deaths: complacency. In the first few days of 1904, fire standards were immediately updated all over the country, and theaters were closed until they complied. The standards were even enforced—for a while. The problem is, fires are rare. People get lax on safety requirements because fires usually don’t happen, so empty sprinkler pies and locked exits are usually not a problem. Until they are.

So it makes sense that the Nederlander Theatre is said to be one of the most haunted places in the world. But it’s not just the theater. In fact, the alley behind it might be even worse. Known as “Couch Place,” but nicknamed “Death Alley,” it was the site of some of the Iroquois’s fire escapes.

Now, if you’ve been to the Midwest in December, you know that anything metal several stories off the ground is going to be icy. And remember that smoke that couldn’t get out of the skylight? Well, it found those open fire escape doors and started pouring into the alley. One of the fire escapes was even installed improperly.

Put simply, the fire escapes were nothing of the sort. People started falling. The first few died on impact with the ground. Later falls were cushioned by the bodies of those who had gone before, leading to some survivals.

It’s no wonder “Death Alley” features on Chicago ghost tours! And why the Nederlander can claim more ghosts than any other theater.

And now for some fiery writing prompts!

- On with the show. Theater ghosts take various forms, from friendly to frightening. Some ghosts seem to like to watch shows and are actually good luck, appearing on opening night when a show is destined to be a roaring success. Sometimes the ghosts of actors inhabit the theaters they loved and give advice to current performers. Other ghosts belong to actors killed in the theater by a jealous lover or enraptured fan, and their presence can be mischievous or even threatening. So what would happen when 600 people die in a theater all at once? If they all became ghosts, the theater could be incredibly paranormally dangerous. If only a few linger in the theater after death, why these few? Did they die in a particularly awful way? Were they the youngest or oldest deaths? Did they have some relation to the theater to begin with?

- An actor’s life for me. You could write a story from the point of view of one of the actors rather than the audience. Instead of just fleeing the theater, an actor is close to the fire and must try to help put it out. They might risk injury doing so. They might also need to rescue other actors in hard-to-reach places: in the Iroquois, one actress died because she was on wires above the audience and could not be rescued in time. Another actor burned his hands by repeatedly taking a stage lift up and down to rescue actors stranded in dressing rooms. Unfortunately, actors who survived lost all their costumes and scenery in the fire—which meant they also lost their jobs.

- Those left behind. Many literary stories describe a family or town affected by a tragedy, such as a deadly fire. In this case, the loss of many women and children would affect families in a devastating way. Funerals would give way to lawsuits and trials, and expose divides in communities. Your story could be told from the point of view of a grieving family member, lawyer, town official, injured survivor, doctor, or even one of the visiting actors mourning the loss of coworkers.

- Medical drama. Your story could focus on a hospital dealing with a mass casualty event, and characters could also include the local press. Start with some interpersonal drama so we get to know everybody, then bring on the disaster. Some staff may have loved ones in the theater and have to hope they don’t find them on an ambulance. Others will be desperate to find the cause of the catastrophe, which may be unknown for a long time. Finish up by having a doctor fall in love with an injured survivor, and you’ve got a good drama on your hands.

- Fix-it. Let’s end with the less realistic: a deadly fire might make a good superhero or supervillain origin story. Their powers could be related to fire and smoke, which they use to either fight fires, cause fires, or rescue people from fires. Maybe their secret identity is a firefighter or paramedic, arson investigator or doctor on the burn ward. The superpowered fire itself could also have a strange origin story: arson, lightning, or even a meteorite.

Thanks for spending your Weird Wednesday here! Remember, always be aware of your nearest exit.

Want to chat about the blog? Did you use one of the prompts? Hit me up on social media.

If you like hauntings, you can check out my free story The Impossible House, which won first prize in an On the Premises contest. A woman seeks help from a necromancer after her sister vanishes inside a haunted house.

Sign up for my free monthly newsletter and never miss a blog post! Or subscribe by RSS

Brandt, Nat. Chicago Death Trap: The Iroquois Theatre Fire of 1903. Southern Illinois University Press, 2003. On Goodreads

Hatch, Anthony. Tinder Box: The Iroquois Theatre Disaster 1903. Academy Chicago Publishers, 2003. On Goodreads

Iroquois Theater official website

Major American Fires: Iroquois Theater Fire- 1903: Massasoit Community College

The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever: Smithsonian Magazine

The Fire at the Iroquois Theatre, Chicago: Stage Beauty

Iroquois Theatre Fire: Wikipedia

The Iroquois Theatre Fire: Windy City Ghosts

One of the ‘most haunted places in the world’ is in Chicago — and you may have been there: NBC 5 Chicago

The Nederlander Theatre: Wikipedia